The Nose Knows: A Conversation on Perfume, Science, and Leadership

Recently, I was coaching a senior executive at a well-known luxury goods conglomerate. During a brief aside in our conversation, we found ourselves discussing “the Nose”—a crucial figure in the world of perfumery, responsible for the artistry and science of fragrance creation.

Perfumery is a highly specialized profession that requires years of dedicated training and an exceptional sense of smell. These professionals, known in the industry as “Noses,” are responsible not only for crafting the signature scents that define luxury brands but also for preserving the consistency, safety, and integrity of these formulations over time.

There are only a limited number of such perfumers in the world. They are rare talents, often with finely tuned olfactory abilities that border on the extraordinary. The role of the executive I was coaching included safeguarding the well-being and working conditions of these professionals, ensuring their ability to perform at their best within an environment that respects the delicate balance of creative freedom and regulatory responsibility.

As our conversation deepened, we touched on a fascinating historical figure: Tapputi-belat-ekalle. Some scholars believe she may have been the very first recorded perfumer in human history—and notably, a female chemist. What we know of her comes from inscriptions on fragments of clay tablets dating back to the Middle Assyrian period, more than 3,000 years ago.

These inscriptions reveal that Tapputi held an influential role in the Mesopotamian court. Her title, “overseer of the palace,” suggests she led a collective of female expert perfume makers—referred to as muraqqītu—who were tasked with preparing fragrances for the king and royal family. The texts describe not only her leadership but also her technical expertise in aromatic compounds.

Some of these cuneiform tablets, on display today at the Vorderasiatisches Museum in Berlin, even detail one of Tapputi’s perfume-making processes. She and her team worked with aromatic and medicinal plants and flowers, many of which were abundant in the region at the time. Through complex distillation and extraction techniques, they created scented oils for ceremonial and possibly therapeutic use.

What’s remarkable is that while the tools and scale have changed, many of the techniques Tapputi used remain relevant in modern perfumery. Today’s perfumers still rely on extraction methods and natural ingredients—though modern chemistry and technology have refined and accelerated these processes considerably. (For a glimpse into this world, the documentary Nose offers an intimate portrait of François Demachy, the long-time in-house perfumer at Dior.)

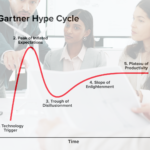

My coachee went on to speak about the future of perfumery, particularly ongoing research into so-called “e-noses.” These are electronic devices capable of detecting and identifying volatile molecules, much like a human nose does. They produce a kind of “fingerprint” of a scent—a molecular profile that can be used to characterize and differentiate samples.

Although initially developed for perfumery and flavor industries, the applications of e-noses are now expanding rapidly. One exciting frontier is in healthcare: these devices are being tested for non-invasive diagnostics, where changes in the volatile molecular profile of a person’s breath could indicate metabolic conditions, such as fluctuations in blood sugar levels. This could lead to new tools for the early detection and monitoring of diseases.

E-nose technology is also proving valuable in food safety and quality control. As food spoils, its chemical profile shifts—something an e-nose can detect far more quickly and consistently than the human nose. This offers promising possibilities for supply chains and food production systems, where shelf life and freshness are critical factors.

In addition to technological advances, modern fragrance research is exploring the psychological dimension of scent—an area that is both profoundly human and surprisingly under-researched. We are just beginning to understand how and why certain smells evoke powerful emotional responses or unlock deeply buried memories. The reason, it turns out, lies in the unique neurological pathway that connects our olfactory system to the limbic system, the part of the brain that processes memory and emotion.

This explains why the scent of jasmine might transport someone to a childhood garden, or why the smell of paper and ink can suddenly rekindle a desire to curl up with a good book. Certain fragrances can calm, invigorate, or even inspire us—sometimes without us fully realizing why.

What began as a casual aside in our coaching session turned out to be a deeply insightful exchange. Understanding the intersection of tradition, innovation, and sensory perception gave us a richer lens through which to explore leadership. For my coachee, this conversation later proved to be more than just a curiosity. Not long after, they stepped into a new role as general manager of an organization dedicated to these very frontiers of olfactory science and technology.

It was a reminder that leadership often takes shape in the spaces we don’t always plan for—in side conversations, subtle recognitions, and shared reflections. From ancient Mesopotamia to molecular diagnostics, from the psychology of scent to the stewardship of rare expertise—what surfaced was a broader understanding of how influence and decision-making unfold in fields where subtlety, precision, and complexity matter deeply. In such contexts, leadership is less about control and more about sensing what needs to be nurtured, protected, and allowed to evolve.

Explore the leadership and executive coaching services we offer

Discover how Executive Coaching @ The Hubler can guide you toward a renewed sense of purpose and sustained success. Explore the leadership and executive coaching services we offer and reach out to discuss the approach that best aligns with your aspirations.